I was never particularly engaged in Shakespeare’s plays when I was at school. In fact, they outright perplexed me. I agonised over every word on the page, trying to understand what he was saying. In the end, the joy of reading was lost. This is a common experience amongst students, many of whom groan at the very mention of Hamlet or Macbeth.

Disrupting students’ preconceived ideas that Shakespeare is boring, too difficult or irrelevant is often the first challenge for teachers. With so many resources available, it can also be difficult to know where to start. Below are what I believe to be the key tools to frame a unit of Shakespearean study to make it accessible and enjoyable for all students.

Many of the following insights and activities are based on Harvard’s Project Zero Visible Thinking techniques, which helps students to bring their thinking to life, and The Royal Shakespeare Company’s process drama techniques, which enable students to have fun with Shakespeare, step into characters’ shoes and ultimately connect with the text in a meaningful way.

Ditch the table and chairs

Remember that Shakespeare’s plays were performed in an immersive format with the intention of creating stories that the audience could feel and experience. For this reason, a normal classroom setup just won’t cut it. This isn’t to say that some lessons won’t have students writing at desks. But shifting the layout of your classroom and giving students the physical space to step into the shoes of Shakespeare’s characters will open up many possibilities for engagement and understanding.

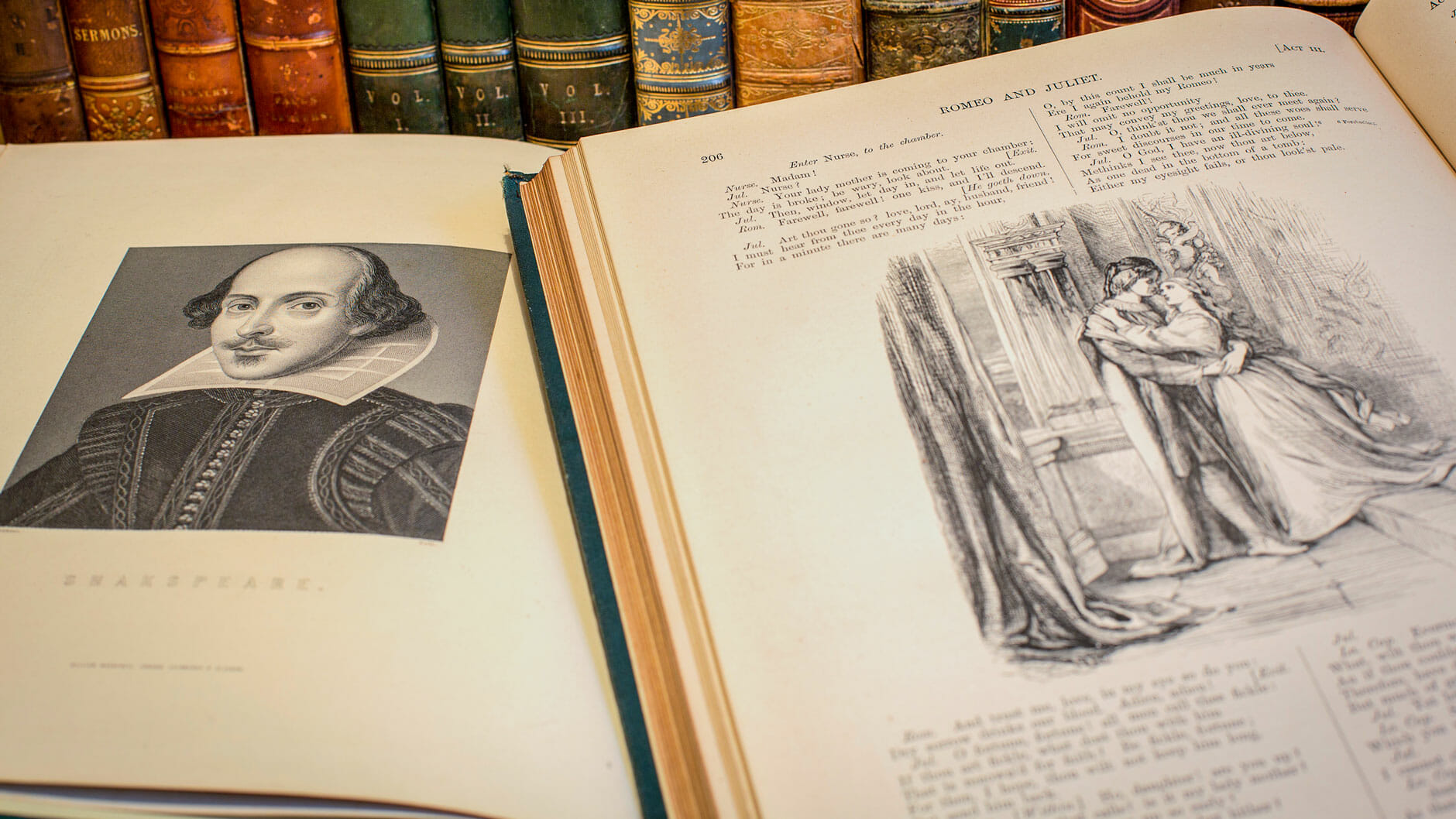

Consider beginning your unit of study by exploring William Shakespeare’s world and his relevance today. Push back tables and chairs and set up the classroom to mirror The Globe Theatre to engage students. Transport them back to Shakespearean times by having your students sit in the pit, the galleries, etc. They’ll be able to better understand the pivotal social importance his plays have had for centuries — the fact that he wrote for the masses and that his work can be enjoyed by everyone. Ask students to research the times in which Shakespeare lived, and his contributions to the English language. Students could also research some of the words or phrases developed by Shakespeare and use these in a creativity activity, such as a written piece or an interview of their classmates. Activities such as these will help students build confidence working with Shakespearean language.

Create an overview of the text

Tap into students’ prior knowledge about a Shakespearean play or piece together the main plot and characters as a class. Give students an overview of the play to help establish some level of confidence. There’s no better way than an activity called a Whoosh! This is one of many process drama techniques devised by The Royal Shakespeare Company that are exercises used by actors when preparing a performance. In a ‘Whoosh!’, the class forms a circle with the teacher on the outside reading a brief, abridged version of the text. This activity allows you to outline the story and central ideas while the students embody the various characters and objects in a playful way via facial expressions and body language. It’s important to emphasise that students will not be assessed on their acting skills, but rather their engagement with the exercise.

A great summary video from The University of Warwick can be watched here. This kind of kinaesthetic learning allows students to not only understand some of the words of the play, but experience them and feel their impact.

Work with language and focus on meaning

Workshop key vocabulary with students — Shakespearean words that will either reappear throughout a play or phrases that are central to their understanding of a text. Building a vocabulary list may also help encourage ownership of the play and act as a helpful reference point.

Unless you’re teaching a particular sonnet or a passage analysis, it’s more important to focus on the overall meaning of the play, rather than a literal translation. Otherwise, students might miss the central ideas, motifs and character development within the story. Have students create summaries at the end of each scene. Depending on the purpose of your unit and year level, not every scene has to be studied in depth to gain a meaningful understanding. For one act of a play you could divide students into groups and assign scenes that each group could summarise and teach to the rest of the class.

Consider using some Visible Thinking Routines to unpack key passages or character speeches. For example, the See Think Wonder routine is a great way of bringing the thinking of characters and students to life. Firstly, ask students to record the key objects, symbols and characters referenced in the passage. Secondly, have them list their interpretations of what they think the character is saying. Finally, ask them to record any questions they have or things they would ask the character. Giving students time to work through a passage individually or in pairs will lead to a richer class discussion.

Relate universal themes to students’ own lives

One of the many reasons Shakespeare is still so commonly taught in schools today is that his themes are timeless. We therefore want students to realise how the ideas that are central to his plays — revenge, love, betrayal, loss — are also central to the human experience.

When teaching a Shakespearean play, I often centre each lesson on a particular theme and start the class with a quote that relates to that idea. I then use the three levels of reading technique, asking students to unpack the quote on a literal, inferential and evaluative level where they relate the idea to Shakespeare’s play, as well as to their own lives and experiences. We then return to the initial quotation at the end of the lesson to see what new understandings have been gained.

Step into the shoes of characters

Perspective-taking exercises help students understand characters’ motives and enable them to write more insightfully. Freeze frames are a great tool for achieving this goal and for encouraging collaboration amongst students. In this exercise, students are given a key scene from a play and asked to work in groups to create frozen images using their facial expressions and body language. Each scene then unfreezes for a few seconds as the characters interact or speak a few lines of Shakespearean dialogue. Activities such as freeze frames can then be followed by a writing exercise. Students could write from the perspective of a character, a letter between characters or a reflective piece analysing their frozen scene.

A Compass Points Thinking Routine is another tool for helping students understand the dilemmas characters face in Shakespeare’s plays. In this activity students draw a compass and consider four different points of a proposition. For example, should Hermia run away with Lysander or should Friar Lawrence be held accountable for the death of Romeo and Juliet? The four points of the compass ask students to consider the advantages, disadvantages and missing information in the proposition. Finally, they must come to a conclusion or develop advice for the character. These kinds of activities break down complex ideas for students and help them to analyse an aspect of the text in stages.

Bring the setting to life

I’m often told by students that the world of Shakespeare, with its swords, Old English and arranged marriages, are just too far removed from their reality. Exploring the setting of a play is therefore vital to help students enter the world of the text. The Royal Shakespeare Company suggests ‘Guided Imaginary Journeys’ as a way of bringing the setting to life. This is an exercise where students work in pairs. In this scenario, one person is blindfolded and led around the room by their partner through the setting of the text. For example, a student may be led through the sights, smells and sounds of the heath of Macbeth where we first encounter the witches. Props or costumes are not needed for this exercise. Students use their language, imaginations and detailed knowledge of the text to transport their partner into the world of the play. Following this activity, students could develop a poem in which they incorporate the mood of the setting, as well as the characters and objects they encountered in their guided tour.

These activities are interchangeable and can be adapted when teaching other texts. The aim is to get students on their feet so that they can step into the play, breaking down heavy themes into relatable, manageable exercises, and understanding the material on a deeper, more meaningful level. Hopefully you can employ some or all of these activities in your classroom to empower students to have fun with Shakespeare, develop confidence working with challenging material, and ultimately experiment with their learning.